Update > When Tensions Rise: How to De-escalate Politically

When Tensions Rise: How to De-escalate Politically

2026-01-06

When Tensions Rise: How to De-escalate Politically

Tensions rise when conflict escalates, and conflict can escalate in seven ways: ’the number of actors, the tactics and the means used, the nature of the demands, the targets selected, the extension of the geographical area where a conflict is being manifested and an extension in time.’[1] Knowing what caused a conflict to escalate provides insights into the specific situation and allows leaders to determine the most appropriate response. Following the same seven dimensions, political de-escalation can be achieved by reducing the number of actors or reducing the intensity of the tactics and means used, etc.

Processes of escalation and de-escalation in conflict are unpredictable. Conflicts are often viewed as linear processes, where peace naturally emerges after a period of conflict.[2] In reality, conflict is chaotic and messy, not linear. The seven dimensions above can be useful in understanding the processes of escalation and de-escalation, but leaders still have to consider the complexities in the specific situation and adjust the de-escalation strategy accordingly. For example, if the conflict escalates over a geographic area or the number of actors increases, a local ceasefire might be a good strategy to de-escalate.

Ceasefires can be a wise strategic decision, but they demand careful consideration, as local ceasefires could also cause further escalation.

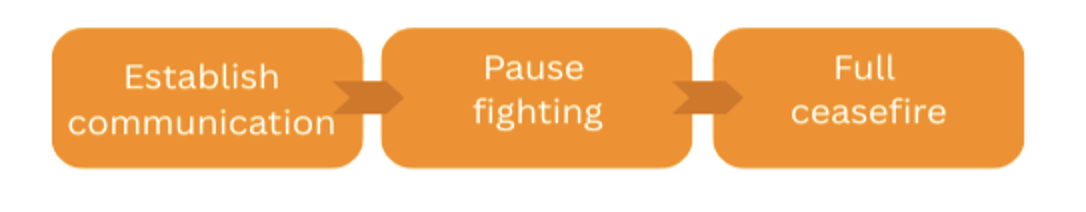

Local ceasefires are more likely to be successful if they are between groups that have successfully negotiated before and have established a level of trust. The ceasefire can be a stepping stone to building more trust and credibility between groups that did not previously negotiate. Ceasefires that are gradually implemented are more likely to be successful and promote trust and transparency. Start by establishing communication and forming agreements, then pause fighting in certain areas, and slowly build to a more extensive ceasefire agreement that protects civilians, bans certain heavy weapons, or includes other agreements that would benefit the region. If the ceasefire is successful, the pause in fighting can influence positive behaviour in the surrounding areas, which can also lead to a decrease in fighting in nearby regions.[3.

On the contrary, conflict actors may choose to enter ceasefires for devious motives. For example, pausing fighting in one area to free up troops to fight in other areas. Similarly, a ceasefire may be used to rearm and regroup soldiers for a future attack. A ceasefire can be used to consolidate territorial control, it freezes conflict lines and allows organisations to focus on strengthening government structures and increasing legitimacy with local populations. If consolidating territorial control is the motivation for negotiating the ceasefire, rather than a future of peace, this can be harmful to the success of the ceasefire.[4]

Listening Strategically in Politics

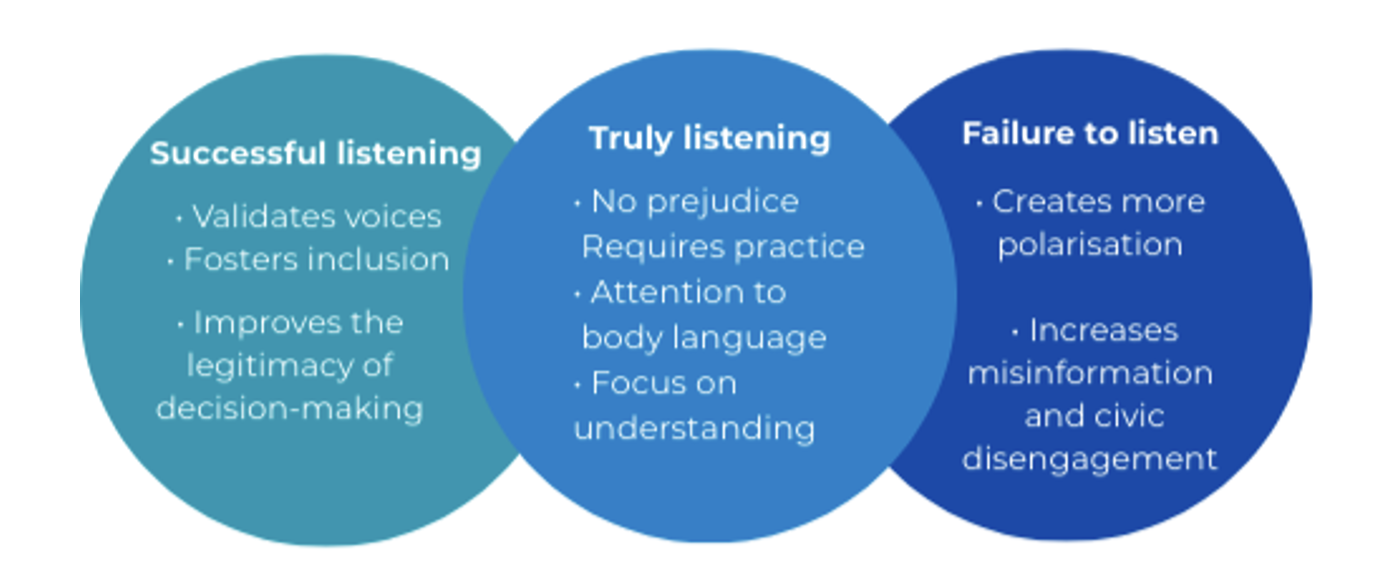

Listening strategically means paying attention to which voices are louder than others, and which voices are not heard at all. Listening is more than hearing; truly listening requires practice, to let go of prejudices and listen with an open mind, aiming to understand what the other is saying. Strategic listening means recognising the power imbalances in how different voices are heard, and aiming to pay extra attention to silenced voices and attempting to amplify them. In politics, there are more dimensions of listening to take into account. ’When politicians and citizens truly listen, they validate voices, foster inclusion, and enhance the legitimacy of decision making.’[5] On the other hand, ’failures in listening exacerbate polarisation, misinformation and civic disengagement.’[6]

Strategically listening includes paying attention to more than voices alone; body language and actions can be loud communicators. For example, a minority group in Botswana, the Ncoakhoe, leave a settlement or village when another group moves in, and then migrate to areas where there is no one to cause conflict. The action of moving away clearly communicates the difficulties they face and their desire to live in peace.[7]

When citizens feel heard by politicians, it increases trust and, with that, the legitimacy of political leaders. Truly listening requires empathy and compassion towards the person speaking. Moreover, listening strategically requires understanding how minority voices might be interpreted differently; that is why listening without prejudice is so important. A practical example is from the World Humanitarian Summit (WHS). The summit invited Global South participants to speak, but without corresponding obligations for decision-makers to listen. The result was a reform agreement between donors and large humanitarian organisations to accept localisation demands, but without the involvement of the Global South participants who were advocating for localisation.[8] The failure to listen led to a reform agreement that undermined its own objective during formation by not practising localisation principles.

In national and regional politics, similar dynamics can occur. True equality in politics is not achieved by a few minority voices in parliament if their voices do not have equal power to be heard by other politicians or the population. Strategic listening is important both in parliament and when listening to people on the ground.

Reframing Issues, Not People

Political issues are always presented in certain frames. For example, militarisation can be framed as an investment in the protection and safety of people in the area, or as an expensive cost that increases violence and costs lives rather than saving them. When it comes to political issues, politicians have a choice in how to frame the issue. The way politicians frame issues is highly influential in public opinion.[9]Framing people will only lead to more violence and take focus away from finding solutions to the actual problem. Framing issues allows politicians to strategically present their policies and plans in a way that emphasises the alignment with their values and long-term goals.

A harmful approach to framing is creating a scapegoat, blaming a certain group as the source of an issue; this is framing people. During World War 2, the nazi regime framed Jewish people as a cultural threat and as the source of economic issues.[10]This type of framing also happens in the US and several European countries, where right-wing politicians frame migration as the cause for a lack of job opportunities and for poverty in the country. The politicians say migrants ”take jobs from natives”, or they frame migrants as ”lazy people who live off tax money”. Framing people in this way creates more hate and violence towards other groups, while it takes attention away from the issue at hand, like underemployment or problems in the social welfare structure.

If politicians frame people and create scapegoats, it can indicate that they are not focused on finding a solution to the issue at hand and, therefore, may not act in the best interest of the people. Instead, politicians should focus on framing issues according to what values are important to them. The way political parties frame issues is influential in determining what the political debate is about.[11] If healthcare and education are important goals for a political party, they can strategically reframe an increase in taxes as an investment in better healthcare and education.

Frames are not always accepted by the people. Indicators that increase the likelihood of frames being accepted are alignment and resonance.[12] Alignment and resonance refer to the need for frames to align with beliefs and conceptions already present in society, and that resonate with the experiences of day-to-day lives. Simply put, to successfully reframe higher taxes towards an investment in healthcare/education, there needs to be a pre-existing belief that healthcare and education are important. If there is a big gap between the politician’s goal and the existing beliefs of the public, the frame may need to be extended to include more aspects of the themes and issues that the public believes are important.

Negotiating in a Fragile Democracy

Negotiating in a fragile democracy requires extra careful consideration of the risks of negotiating, the motivations of the other party to negotiate, and safety.

The following points and considerations can be helpful to increase the chances of successful negotiations:[13]

- Extensive informal negotiation can lay the groundwork for formal negotiations, like the scope and included parties.

- A reduction in violence by formal ceasefires or a halt in violent acts by the key parties preceding the negotiations.

- For an inclusive negotiation process, not every party needs a seat at the table if they have good relationships with key actors at the table. For example, if civil society organisations can leverage a good relationship with a political party at the table, their interests will be represented despite their exclusion from the formal negotiation process.

Negotiations often occur when the cost of war exceeds the cost of negotiations, or when the warring parties reach a mutually harmful military stalemate.[14] A mutually harmful military stalemate occurs when ‘both parties have come to believe that they cannot practically or successfully escalate the conflict to achieve their goals at an acceptable cost.’[15] Parties are more likely to negotiate when they are in a stalemate, when continuing to fight is costly, but there is no prospect of gain. Parties become open to negotiations when the cost of negotiating is lower than the cost of war.

Examples of the costs of the process of negotiation itself are the fear of losing internal or external support, the risk of legitimising the other party, and whether the negotiating party is reliable.[16] In a fragile democracy and within ongoing conflict dynamics, there are more complexities in negotiations that come with additional risks. Safety is an important consideration, as merely the news about ongoing or starting negotiations can already turn the involved parties into targets and increase security risks.

At the same time, conflict actors need to consider whether the opposing party is serious in their call for negotiation or whether their motives are cynical. Insincere motives to negotiate can be to gain intelligence on the other party, to stall, or for the party's own benefit in increasing their political standing and legitimacy through engaging in negotiations. Substantive negotiations where the parties show willingness to have meaningful discussions on multiple policy issues show they are serious in their efforts to end conflict, even if they do not immediately reach agreements. The act of substantive negotiating shows good intentions.[17]

Building Coalitions from Conflicting Camps

Coalitions are powerful forces in civil wars. Conflict actors are likely to align their efforts and form coalitions when they have a power balance and when their coalition forms a military synergy.[18] When conflict actors share similar ideologies for the future, this also increases their chances of forming an alliance, even though they might be opponents in other areas.

Successful coalitions are dependent on several factors, and not all conflict actors are likely to engage in coalitions with each other. In civil wars, coalitions and collaborative efforts can emerge in different forms. Conflict actors can choose to collaborate in just one area or choose to form an official coalition. This can allow for more collaborative opportunities.

When actors have similar levels of power, it will be easier for them to trust each other, as there is less fear that a stronger party will dominate the coalition. Military synergy occurs when the combined military powers of coalition members complement each other in a way that creates new military value, for example, one party has advanced technology, while the other party excels in guerrilla tactics. Similarly, coalitions that include different ethnic groups are more likely to create synergies because they have access to more resources and have influence in different areas.[19] The more synergies cooperation between different parties will create, the likelier it is for them to engage in a coalition.

Sharing the same ideology increases the likelihood of the long-term success of the coalition.[20] Logically, similar ideologies and views for the future will make the coalition more successful as they can continue to work towards this future together. This does, however, not mean that short-term coalitions between opposing actors who have incompatible ideas for the future cannot work. As long as different actors have a shared short-term goal or can mutually benefit from the coalition in achieving their individual goals, this could be sufficient for them to form a successful coalition. Creating a coalition between opposing parties then becomes a question of what their individual or shared goals are and how they can help each other to reach those goals. Strong coalitions can change the outcome of a war and work in favour of those involved.[21]

[1] Díaz Pabón, F. A., & Duyvesteyn, I. (2023). Civil wars: Escalation and de-escalation. Civil Wars, 25(2–3), 229–248.

[2] Díaz Pabón, F. A., & Duyvesteyn, I. (2023). Civil wars: Escalation and de-escalation. Civil Wars, 25(2–3), 229–248.

[3] Lundgren, M., Svensson, I., & Karakus, D. C. (2023). Local ceasefires and de-escalation: Evidence from the Syrian civil war. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 67(7–8), 1350–1375.

[4] Lundgren, M., Svensson, I., & Karakus, D. C. (2023). Local ceasefires and de-escalation: Evidence from the Syrian civil war. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 67(7–8), 1350–1375.

[5] Scudder, M. F., & Neblo, M. A. (2025). Listening as power in political communication. Political Communication, 42(4), 549–555.

[6] Scudder, M. F., & Neblo, M. A. (2025). Listening as power in political communication. Political Communication, 42(4), 549–555.

[7] Lawy, J. R. (2017). Theorizing voice: Performativity, politics and listening. Anthropological Theory, 17(2), 192–215.

[8] Pardy, M., Kelly, M., & McGlasson, M. A. (2025). The politics of listening at the World Humanitarian Summit – localisation as resistance. Contemporary Politics.

[9] Lefevere, J., Sevenans, J., Walgrave, S., & Lesschaeve, C. (2019). Issue reframing by parties: The effect of issue salience and ownership. Party Politics, 25(4), 507–519.

[10] Bartov, O. (1998). Defining enemies, making victims: Germans, Jews, and the Holocaust. The American Historical Review, 103(3), 771–816.

[11] Slothuus, R., & de Vreese, C. H. (2010). Political parties, motivated reasoning, and issue framing effects. The Journal of Politics, 72(3), 630–645.

[12] Desrosiers, M.-E. (2012). Reframing frame analysis: Key contributions to conflict studies. Ethnopolitics, 11(1), 1–23.

[13] Bell, A., & Aslam, W. (2025). Threads of peace: Leadership and conflict resolution in nested negotiation networks. Negotiation Journal, 41(2), 128–167.

[14] Cao, R. (2024). Personalism and negotiation during civil conflicts. Journal of Global Security Studies, 9(3)

[15] Kalin, I., & Abduljaber, M. (2020). The determinants of negotiation commencement in civil conflicts. Journal of Conflict Transformation and Security, 8(1), 86–112.

[16] Kalin, I., & Abduljaber, M. (2020). The determinants of negotiation commencement in civil conflicts. Journal of Conflict Transformation and Security, 8(1), 86–112.

[17] Cao, R. (2024). Personalism and negotiation during civil conflicts. Journal of Global Security Studies, 9(3)

[18] Steinwand, M. C., & Metternich, N. W. (2022). Who joins and who fights? Explaining tacit coalition behavior among civil war actors. International Studies Quarterly, 66(4).

[19] Steinwand, M. C., & Metternich, N. W. (2022). Who joins and who fights? Explaining tacit coalition behavior among civil war actors. International Studies Quarterly, 66(4).

[20] Gade, E. K., Gabbay, M., Hafez, M. M., & Kelly, Z. (2019). Networks of cooperation: Rebel alliances in fragmented civil wars. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 63(9), 2071–2097.

[21] Gade, E. K., Gabbay, M., Hafez, M. M., & Kelly, Z. (2019). Networks of cooperation: Rebel alliances in fragmented civil wars. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 63(9), 2071–2097.